Reflection

Blindly I follow this path,

a grey life that seems without end.

Oh, wayward fate!

What have I done?

How did I end up here?

There was only darkness and the sound of the wind rushing past my ears. It took me a while to manage to open my eyes. I felt the world spinning above my head. I was dazed, disoriented, and in pain. Sharp stabs on the right side of my torso revealed a bruise the size of an orange. My knuckles were battered and there was blood beneath my fingernails.

A yellow envelope in the inner pocket of the jacket I was wearing was the only thing I found when I searched myself. Inside it were some banknotes—fifty thousand Colombian pesos in all—an address written on a scrap of paper, and a metal keychain shaped like an electric guitar with a set of keys dangling from it. I looked around, trying to get my bearings or think of something to do. I was in a large city; what appeared to be residential buildings stood about a hundred metres from where I lay. In front of them, not far off, behind me, a few pines and a tall eucalyptus adorned the spot. Beyond that, nothing could be made out save for vacant lots not unlike the one I found myself in.

The sky was blanketed with grey clouds and a freezing wind blew. I walked towards the buildings until I reached a narrow, empty street, perfectly cobbled. I wandered along it for minutes, with no idea in mind, no direction whatsoever, until I saw a taxi approaching. I flagged it down and asked the driver to take me to the address written on the paper. It seemed the most sensible thing to do, even if I had no idea where I would end up. The journey felt long and wearisome. A strong smell of cigarettes flooded the car. I sat in a stupor, nearly asleep. The bald driver talked, but his voice reached me as though from far away; I did not understand a word he said. We crossed the city for what seemed like half an hour, until the vehicle stopped on a tiny street flanked by houses, nearly all of them single-storey, save for two that rose to three levels. The one indicated was in the middle of the block. It was a single-storey building with a somewhat grimy façade, painted a pale pastel yellow. It had a double metal door and a window on each side. I wanted to knock, but could not muster the will. I did not feel safe. I tried to peer inside through the windows, but there appeared to be no one in. I stood there, absorbed, for several minutes, unsure how to proceed. Then I remembered the keychain inside the envelope. There were three keys, and I was certain one of them would open the door to this house. And so, after failing with the first, the second let me in.

The house was in complete silence and gave the impression of being unoccupied at that moment. From the entrance I could see, straight ahead, a long hallway that seemed to go on forever, without a single light. To my left, a spacious sitting room furnished with black leather sofas arranged around a small glass-and-metal coffee table in the centre. To my right, an archway led to another room that was unmistakably a study. Upon entering, I could see that this room was lined with bookshelves on every wall, all crammed with books. Facing the only window, which looked onto the street, stood a large garnet-coloured chair and a finely carved wooden desk rich in detail. On it sat a crystal bottle half filled with a liquid I assumed, from its colour, to be whisky, an empty glass, a photograph of two men flanking a woman, and an envelope identical to the one I had found in my jacket—which immediately seized all my attention.

Opening the packet frightened me somewhat. Everything had been strange enough already, and nothing suggested the outlook was about to improve. I sat in the chair and for a moment stared at the envelope as though a snake poised to strike lay before me. I poured a glass of that whisky and drank it in one go. I hesitated a moment longer. Then I picked up the envelope and emptied it onto the desk. Only one thing fell out—another piece of paper, much like the first. It bore a message almost equally brief, indicating the name of a place: Azucenas Park. None of it stirred the slightest memory.

Stunned, I sank into myself and drifted through my own consciousness. Several minutes passed. I paced the room trying, in vain, to remember something, when beneath the archway a small girl appeared—no more than ten years old. She stood there, her black hair gathered in a braid that fell to her waist, simply watching me.

“Are you David?” she asked.

“Yes,” I said, merely for the sake of answering; I had no idea who David was.

“Papá said you were coming at noon, but it’s only ten,” she went on.

“Oh, right…”

I did not know what else to say to her.

“Is Papá here?” I thought to ask. Something not quite as strong as hope, I innocently felt.

“No, he left last night.”

“Where to?”

“I don’t know. He didn’t tell me anything.”

“What’s your name, sweetheart?”

“Isabel.”

“And your mother?”

“She’s with my uncle.”

I noticed her uncertainty, and I did not know what else to add. I brought the conversation to an end. The girl walked away calmly, down the hallway, with that carefree, trusting air that only small creatures possess. At that moment I felt as full of questions as a five-year-old child. I left the house with little purpose beyond keeping up the role Isabel had assigned me, for I had no idea where to go. I tried once more to coax information from my memory. All I managed was to rekindle the savage headache I had woken with on that wasteland hours before. So I decided to look for a pharmacy or a shop where I might buy some medicine. Leaving the house, I turned right. I walked about three blocks and took several detours. Dizzy with pain, worry and anxiety began to close in on me. I felt hunger and thirst.

I found a small shop on a corner after about five minutes’ walk, I believe. The place was a sort of garage packed with shelves stocked with kitchen products, cleaning supplies, stationery, and a few cold-and-flu tablets. The person behind the counter was a woman of about fifty, short, stout, and rosy-cheeked. She was laughing as she saw off a customer—a tall man in his sixties, but with exceptional vitality. I decided to buy some medicine and something to eat and drink. I asked for two paracetamol tablets, a bread roll filled with arequipe, and a bottle of unsweetened tea. I paid the woman and sat down at a table outside the garage, surrounded by three plastic chairs—originally white, but yellowed with time. The sky began to clear, giving way to a scorching heat that made my forehead sweat.

“I’ve seen you before, haven’t I?”

I had not realised she was speaking to me.

“Pardon?” I replied after a few seconds’ hesitation.

“You’re Doña Sara’s brother, aren’t you?”

I had no idea whom she meant. Seeing my obvious bewilderment, she went on.

“I haven’t seen you around here in ages—not since you all moved to the neighbourhood. I didn’t recognise you; it’s just that you’ve filled out a bit, haven’t you?” As she said this, the woman laughed sheepishly and the red of her cheeks deepened. I felt profoundly uncomfortable and anxious. I did not know what to say; all I could manage was to laugh in an attempt at courtesy and complicity. Then she continued.

“Is the lady doing well? She hasn’t been round these parts in days. Mind you, she never did go out much, did she?”

At that moment, several people arrived at the shop. A man of middling height, rather heavy, with a sparse short beard, carried in his arms a girl of about two who was crying inconsolably and babbling something unintelligible. Behind them came a woman who resembled the shopkeeper, though even shorter and heavier. She appeared to be the child’s mother and the man’s wife. I seized this unexpected visit as my chance to leave. I did not want any more questions and remarks that only fed my uncertainty and anxiety. While the shopkeeper received the baby with great delight and fussed over her in an effort to stop the noisy tantrum, I quietly and carefully picked up my bottle of tea, got to my feet, and walked in the opposite direction from which I had arrived. Two blocks on, I came upon a park brimming with flowers. Some ten thousand square metres filled with assorted, visibly ancient trees and an uncountable profusion of lilies in every colour. The place was a broad expanse of lawn that ended at the walls of the neighbouring houses. Each wall was decorated with large paintings done directly on the brick, all depicting birds just as colourful. There were narrow cobblestone paths winding here and there among the flowers and trees. In the centre stood a fountain with a tall sculpture at its heart, depicting a man carrying a woman in his arms while she reached one hand towards a waning moon carved in marble. Around it, several granite benches. The place was beautiful.

Once more, with nothing useful in mind, I sat down to wait for whatever might come. After all, if nothing came of this place, I could return to the house and perhaps the girl could give me more information, or perhaps the woman from the shop would tell me something else. My wait, however, was not entirely fruitless, for after a few minutes sitting there, a man of about fifty appeared, walking along the street. He was tall, with a kindly, paternal face, pushing a supermarket trolley loaded with thermos flasks. As soon as I saw him, I stood up and went to meet him. He was a coffee vendor, so I bought one from him and drew him into conversation to glean whatever information I could—discreetly, of course.

“Well, friend, the only odd thing I’ve heard is that a young fellow from around here was found dead this morning,” he told me as he poured himself another coffee.

“Did you know him?” I asked.

“Well, to be honest, I’m not sure—one sees so many people…”

“But do you know who he was?”

“All I can tell you is that his name was Juan López. He lived in the neighbourhood with a young woman and an eight-year-old girl. The word is they found him in a ravine somewhere up north. Apparently he’d been at odds with the wife and the brother-in-law. Seems it was the woman’s brother who killed him.”

Without another word, the man continued on his way, followed by the clatter of his trolley. I watched him, half lost in thought, until he disappeared from view. And so, with that news, I decided to head back to the house. Sitting in the study, I sank into a well of unconsciousness. With a glass of whisky and a thousand ideas, conjectures, and questions circling my brain, the minutes passed—perhaps hours—adrift in the shifting ocean of neurons. Although I had no idea who Juan López was, nor what connection he had to me, if any, the news of his death devastated me in a way I could not explain. All I could think was that the girl Isabel was surely his daughter and that she was now an orphan. I poured another glass of whisky and turned my attention to the portrait on the desk, which I had not looked at before. The woman in the middle was about twenty-five, slender, very fair-skinned, with straight black hair that reached almost to her waist. She had her arm around a man on her right, about thirty, a little taller than she, dark-complexioned and somewhat stocky; on the other side stood another man who appeared to be the youngest, with skin as pale and hair as short and black as hers. All three wore broad smiles. I picked up the frame and examined it. After turning it over a few times, it slipped from my fingers and, hitting the floor with a sharp crack, broke apart. I managed to extract the photograph. On the back, something was written. The message read:

Sara, I hope you and Juan can enjoy your new home and that the baby on

the way will be a joy for the whole family. Thank you for making me an uncle.

This was the best photo I could find from our trip to Madrid.

A big hug and a kiss. I love you very much.

David.

I stared at the photograph a while longer. I thought of going to find Isabel; I would speak to her, hoping to find some answer. I left the photograph on the desk and walked out of the study, heading towards the hallway. Halfway down that corridor there was an open door—it was a bathroom. I stopped in front of it. It dawned on me that in all the time since I had woken, I had not been able to see what I looked like; my own face was still unknown to me. So I stepped into the bathroom, where there would surely be a mirror. I switched on the light and stood before the washbasin. An oval mirror framed in bronze hung above the tap, level with my gaze. For the first time, I could see myself. I had several small cuts all over my face, like scratches. My skin looked white; I was pale, as though ill. My hair was dishevelled—short and jet black.

Beyond the details I could make out on my face, there was only one thing that struck me and that provided at least one answer to my questions: I was David.

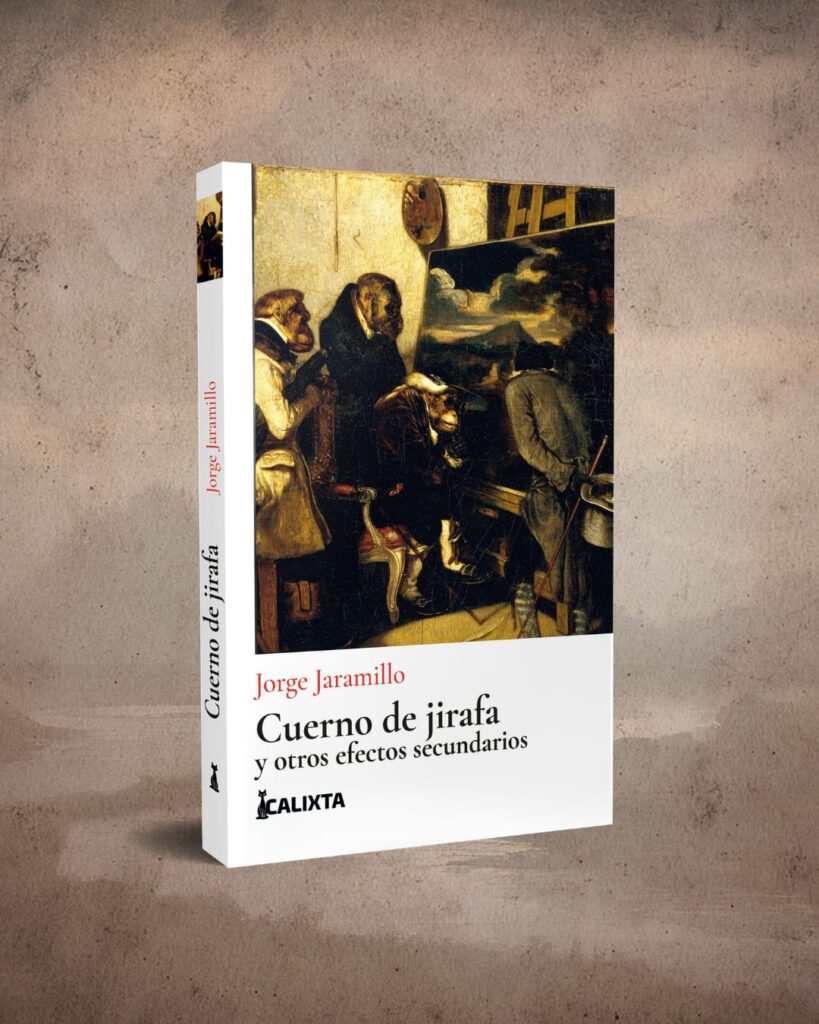

ENJOYED THIS STORY?

Find this one and thirteen more in

Cuerno de Jirafa y otros efectos secundarios

What starts as an ordinary day rarely ends that way